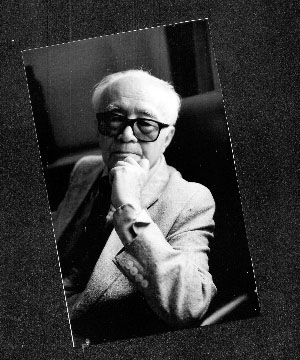

1587, a Year of No Significance (traditional Chinese: 萬曆十五年; pinyin: Wanli Shiwunian) is Chinese historian Ray Huang's most famous work. First published by Yale University Press in 1981, it examines how a number of seemingly insignificant events in 1587 might have caused the downfall of the Ming empire. The views expressed in the book follow the macro history perspective.

The Chinese title, meaning "the fifteenth year of the Emperor Wanli", is how the year 1587 was expressed in the Chinese calendar: the era name of the emperor at the time, followed by which year of his reign it was.

Although Huang had completed the manuscript by 1976, no publisher would accept it at first, as it was not serious enough for an academic work, but was too serious for popular non-fiction.

The work has been translated into a number of different languages: Chinese, Japanese, German and French.

One of the GREAT books in the China

Paul Frandano,

Scholarly work that is easily accessible to non-specialists, historian Ray Huang's(黄仁宇) ironically subtitled 1587: A Year of No Significance focuses on the Ming Emperor Wan-li--who rose to the throne and the age of eight and who reigned for 48 years--and five other figures in the court of the decadent, doomed Ming Dynasty. This is an off-beat masterpiece of both history and biography, learned yet chatty, steeped in the dense, ancient imperial chronicles yet surprisingly contemporary in its oblique illuminations of contemporary Chinese political culture through the prism of history.

Huang's approach is reminiscent of Kurosawa's in Roshomon, employing multiple points of view from the imperial court in seeking to expose and foreshadow the demise of the Ming. We meet archetypes from the drama of Chinese history: the Machiavellian chief minister, the perceptive but disregarded general, the anguished philosopher, and, at the story's center, the eccentric Wan-li emperor himself. In choosing to write about Wan-li, Huang is able to create a measure of narrative tension unusual in Chinese historical writing, because by the Year of the Pig, 1587, the emperor has ceased to fulfil his prescribed role in rite and ritual as the embodiment of moral order. Wan-li's behavior causes great agitation among his courtiers, bureaucrats, retainers, imperial wives and concubines, eunuchs, and slaves, each of whom occupies a carefully defined place in the regimented life inside the walls of the Imperial Compound and who, without punctilious observances by the emperor, is without a fixed point of reference.

A special feature of this book is the wonderful chapter on the incorruptible censor Hai Rui, who dared impeach the Emperor. Hai Rui is familar to students of modern

Although published by a major university press, 1587: A Year of No Significance is not simply for specialists. (It is, however, highly regarded among professional

A variety of excellent, biographically-based popular works on imperial China remain in print--Jean Levi's historical novel, Emperor of China, and Jonathan Spence's work on the Qing emperor Kang-hsi are among the best known--but, in my opinion, Huang's book surpasses them all. 1587 is, indeed, a work of great significance, by an author of encyclopaedic knowledge and scope and a stylist of vast charm and elegance.

A reviewer above has already done an excellent job of summarizing the book, so I can only hope that my review can serve as a complement. "1587" is essentially an examination of why the Ming dynasty--an institution that commanded great wealth and governed a vast nation--was already showing signs of decay and its impending collapse under the reign of the Wanli emperor. Ray Huang does an excellent job to show how cultural inertia and an institution that governed miserably effectively neutralized the voice and power of individual participants. The Ming dynastic system did not tolerate loyal opposition and was not designed for ministers or individuals to discuss opposing views in an orderly manner, which meant that power struggles were bound to be ugly as rival ministers and bureaucrat employed moral arguments to tarnish each others' reputation. Avenues for advancement within government amounted to a zero-sum game in which an official's effectiveness in governance was a barometer of his morality (bound with tradition and Confucian precepts open to interpretation). Imagine if your local mayor was judged not on his or her effectiveness or merit, but on whether he or she was a morally upright individual who was adhering to both the spirit and traditions of the past.

The Ming imperial system also placed a greater value on the institution and sought to dehumanize the emperor. The emperor was the emperor--he was not Wanli, not Jiajing, etc. The bureaucrats and officials--whose power was constrained individually--exercised great power as a group, effectively dictating how the emperor should act, behave, and present himself to the public. Little wonder then, that the Wanli emperor, whose power was in the negative and not the positive, hardly sought to rule in an effective manner after being weighed down by such an institution. Others in the drama--the powerful minister, the innovative general, the eccentric bureaucrat, and the dissenting scholar--would find the same forces inhibiting their ability to affect real changes.

Huang ends his book by concluding that the Ming dynasty was a "highly stylized society wherein the roles of individuals were thoroughly restricted by a body of simple yet ill-defined moral precepts, [and that] the empire was seriously hampered in its development, regardless of the noble intentions behind those precepts. The year 1587 may seem to be insignificant; nevertheless, it is evident that by that time the limit for the Ming dynasty had already been reached. It no longer mattered whether the ruler was conscientious or irresponsible, whether his chief counselor was enterprising or conformist, whether the generals were resourceful or incompetent, whether the civil officials were honest or corrupt, or whether the leading thinkers were radical or conservative-in the end they all failed to reach fulfillment. Thus our story has a sad conclusion. The annals of the Year of the Pig (1587) must go down in history as a chronicle of failure."

I recommend this book for all those not only interested in the history of the Ming dynasty, but to those who are interested in the nature of Chinese imperial statecraft and the question of how government should be structured.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

- 2009-06-24 - 廖氏愤青教材(转载)

- 2009-04-08 - 天使乎,白狼乎?

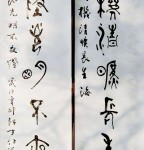

- 2009-01-07 - 丁仕美的君子风 - 转载

- 2008-12-19 - 从历史看儒家文明的生命力

- 2008-12-04 - 司徒雷登:别了六十年还要回来

- 2008-11-23 - 晋豫之行日记(2)- 萧功秦

- 2008-11-22 - 晋豫之行日记(1)-萧功秦

- 2008-10-24 - 叫洋人大开眼界-转载

- 2008-10-19 - 我该买什么样的房子?

- 2008-10-08 - 都缺个陪聊的儿女